Mountain Car Challenge

IntroductionPermalink

To quote the OpenAI Gym page, the challenge consists of:

A car is on a one-dimensional track, positioned between two “mountains”. The goal is to drive up the mountain on the right; however, the car’s engine is not strong enough to scale the mountain in a single pass. Therefore, the only way to succeed is to drive back and forth to build up momentum. Here, the reward is greater if you spend less energy to reach the goal

The problem was first proposed by [[Andrew Moore]] in his PhD thesis and is now a standard testing domain in reinforcement learning.

One can see that for an algorithm that relies on a continuous reward variable, the mountain car poses a difficulty. There is a single reward for scaling the mountain pass but no intermediate rewards, which might guide refinforcement learning. Positions close together on the contiuum may well have completely different optimal responses, depending on the car’s height above ground (potential energy) and often reversing away from the goal point at full speed is globally optimal (you’ll get to the flag fastest) but locally problematic (you’re running away from the goal-point).

MethodPermalink

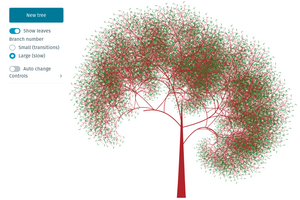

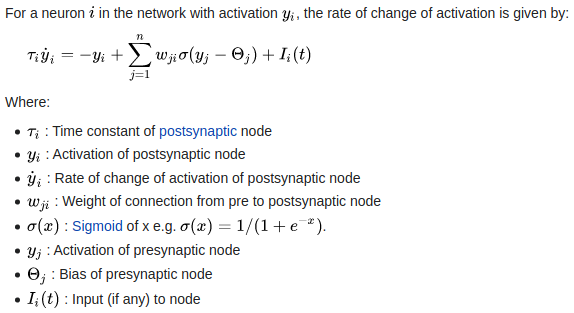

It struck me that a time-based system that could fine-tune the mountain car’s response and engage with the dynamics of the challenge should be very capable here. A continous-time recurrent neural network seemed perfect for the job:

An evolutionary algorithm (genetic algorithm/GA) would be used to search for good solutions/phenotypes where the required phenotypes were CTRNNs with input neurons providing the mountain car’s position (in the x axis) and velocity (positive towards the goal flag).

To power the mountain car we could either define a right and left motor neuron and subtract to get the car’s thrust or use a single motor neuron with outputs mapped from -1 to +1. The latter approach worked perfectly and provides simpler analysis.

| As is usual for this [[Open AI Control Challenges | collection]] , evolution was allowed to explore the space of neural network connectivity as well as the standard weight, time-constant, activation threshold etc. parameters. A goal was to push the system as low as it could go to enable analysis and, with any luck, commensurate understanding. |

ResultsPermalink

Although the original mountain car controllers have inputs providing the x position and velocity of the car, it turned out that the velocity input was redundant for evolved CTRNN controllers. Given the imperative to make networks that are as simple as possible to analyze, the velocity sensor was ablated (set to 0 throughout the trial).

Dual motor, single sensor controllers proved very easy to evolve, taking a few minutes on an Intel Core i5 laptop.

Dual motors, single sensorPermalink

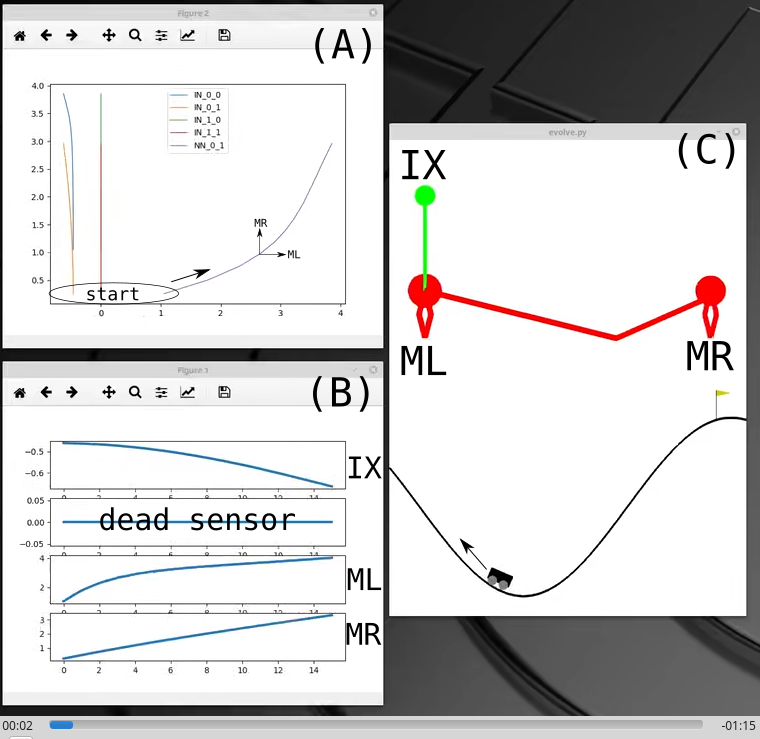

The figure below shows a few windows, cobbled together with Python:

- (A) - By plotting the activation of the input and motor neurons against one another we can trace the movement of the controller network in phase-space over the course of the trial. Here the key interaction is that between the two motor neurons ML and MR.

- (B) - The time-series of the input sensor (X) measuring the car’s x position and the two motor neurons driving it left and right.

- (C) - The animated mountain car and its evolved CTRNN controller.

Here’s some video of the controller taking the car to the flag:

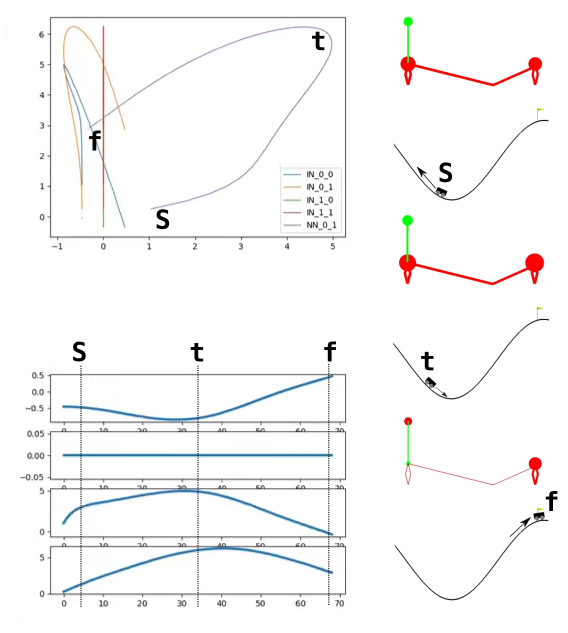

In the figure below we see the mountain car’s neural activation for an single run. Focusing on the interaction between the motor neurons, three events are shown: S the start of the trial, t the trigger point, when the car switches from motors left thrust to motors right thrust, and f the finish of the trial.

As the car starts its left motor receives positive stimulus from the single input sensor, measuring the car’s x position. The x position is negative relative to a central axis and the link weight is negative, resulting in a positive effect. This stimulus drives the increase in MLs activation from s->t . While doing this the left motor is also driving up the activation of the right motor through a positive link. Both motors are self activating, through a recurrent connection.

At t , the trigger point, the activation of the right motor starts to overwhelm that of the left. This causes the car to switch direction of thrust, causing the car to start moving towards the flag. As it moves the x position input sensor reduces its stimulus of the left motor, amplifying the effect of the right motor and causing the car to accelerate towards the finish. At f it reaches its goal with a much reduced left motor.

There are a number of subtleties to the controller, to do with time-constants and other temporal dynamics but the main switch is clearly demonstrated. The car can start from any of the randomised challenge states and achieve near optimal performance.

In an attempt to simplify the system even further, what about having a single motor output, where negative values indicate a left thrust and positive a right? With a single input sensor this represents the simplest possible CTRNN controller conceivable. It turned out evolution had an easy time finding these.

Single motor, single sensorPermalink

Controllers were easy to evolve using the single input sensor, measuring the car’s position on the x axis (negative activation for negative x). These were suboptimal in terms of the energy required and time to flag. Here’s an example of such a controller:

Using a velocity sensorPermalink

The mountain car provides two inputs by default, the car’s x position and velocity. Swithting to a velocity sensor produced much more effective controllers, most sharing a similar principle. It is always gratifying when random populations converge on similar controllers…